IntelliFrosh: Behavior-Based AI for the Frosh

(And everything else in the game)

[Rob Note, Jan 2026: I'm going to keep this intact for posterity, even the bits that make me cringe. Some of it is wild to read as I work in partnership with my friend Claude resurrecting this site. All of this was written mid-1999.]

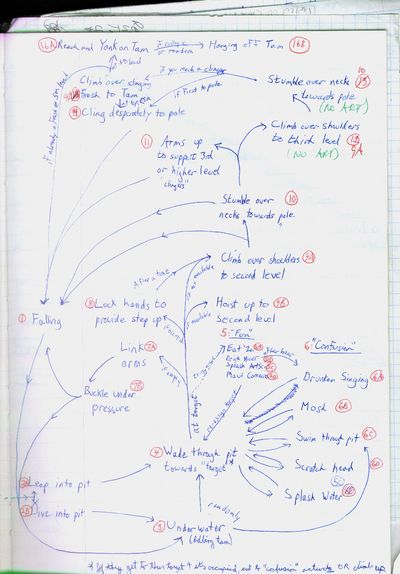

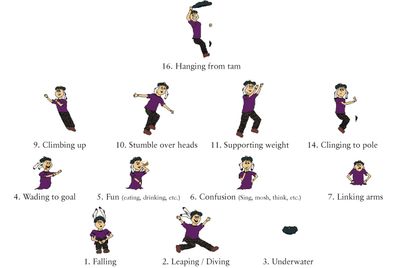

Rob Burke writes: The behavior of the Frosh character is governed by about 30 behaviours that span over 5,000 lines of code. The specifics of these behaviours changed over the course of the project, but for the most part the Frosh behaviours have held true to the ideas I hashed out back in the winter of 1996. This directed flow diagram shows how the original behaviors we decided on fit together. (Click on the image to view it in more detail).

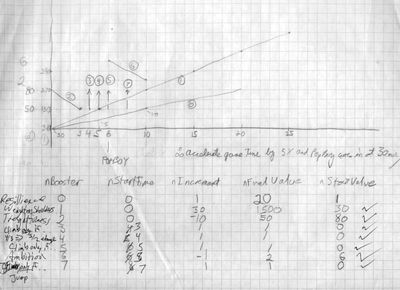

Each Frosh also keeps track of eight integer-based and six boolean "properties," ranging from their resillience and ability to sustain weight on their shoulders to their thoughtfulness when approaching a decision and their climbing ambition. In addition, there are a number of "global" properties -- such as morale -- that fluctuate as the game progresses.

These characteristics tend to improve as the frosh gain experience, and they're also affected by events that the player can trigger during the game. A frosh that you keep beaming with apples, for example, is going to be injured temporarily, but come back with a vengence. A frosh that you feed pizza will no longer be hungry. Frosh enjoy splashing ArtScis, but the thrill grows old fast. The 114 Exam makes the Frosh scatter, but their intelligence goes up a notch as they learn from it (by osmosis). And so on.

The "global" properties include eight different "boosters" that affect how the Frosh handle different situations. For example, what should you do if you're on an upper level of the pyramid with only one person above you and someone else beside you. Should you climb up? Hold your ground? Perhaps jump off and reduce the overall weight of the pyramid?

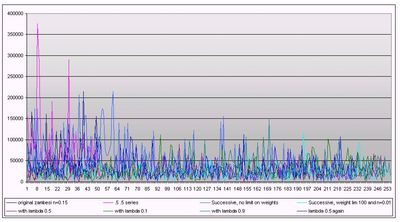

It became clear as development progressed that these sorts of decisions were critical to the evolution of a "teamwork" model among the Frosh. The graph below (with "time" on the x-axis and "value of booster" on the y-axis) shows how the different characteristics periodically improve. The introduction of Pop Boy into the pit (at the 6th time unit on this graph) triggers a change in behaviour that gives the Frosh a much better sense of how to distribute weight throughout the pyramid structure. The boosts that follow coincide with Pop Boy's "lessons" for the frosh.

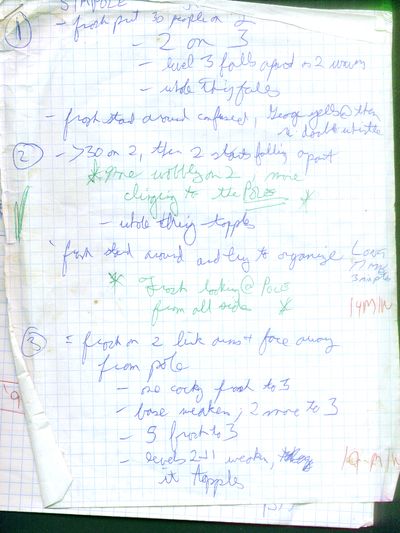

What this doesn't show you, however, is the work that went into making them behave as a team. There was nothing more difficult to code than convincing teamwork. After a year of half-baked attempts, I had a chance to take notes while watching Sci '01 climb their pole. Here's a page from my notes (click on it for more details (like the mud and lanolin)).

I got a sense of a number of things, including the way the Frosh figured out how to get their act together and work as a team. While I considered turning my results into a sort of Stephen Covey motivational video, I ended up using them instead to simulate the slow transition from chaoes to order.

Watch the Frosh the next time you play the game. Their first few attempts will end in dismal failure, regardless of how slack the player is in trying to stop them. Each time they topple you'll see groups of Frosh thinking and regrouping. Notice how each attempt gets them a little closer to the tam and a little bit more like cohesive teamwork. It's pretty cool, but it's not artificial life just yet. That'll have to wait 'til the next project...

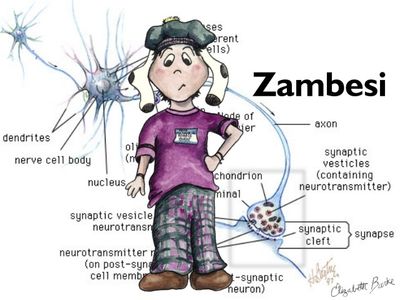

If you're interested in the frosh AI, you might also be interested in a Neural Net extension to the AI I developed called Zambesi (see below).

ZAMBESI: A Neural Net Frosh Brain Upgrade!

What is Zambesi?

Zambesi is an experimental upgrade for the Frosh Artificial Intelligence in Legend of the Greasepole. I implemented it as part of a project for CISC 864, a Neural Networks course.

Zambesi replaces the logic the Frosh use to make decisions with a Reinforcement Learning Network. This network consists of neuron-like units that accept a series of inputs and generate an output that suggests what the Frosh should do next.

The inputs Zambesi uses are simple: the Frosh's distance from the Greasepole, whether or not they're being squished or stepped on, and how high up they've climbed. This information is fed into the network of neurons, which in turn outputs one of five behaviors: climb up, jump down, hold fast, walk towards the pole, or waddle across the pyramid.

The process is called "Reinforcement Learning" because it improves the network's performance by adjusting its neural weights. A similar process governs learning in the human brain.

The algorithm used, called the associative reward-penalty rule, strengthens the neural connections that result in success, and weakens the ones that lead the frosh astray. "Success" and "failure" are measured by a "critic" that observes the pole climb from a distance and provides an evaluation of how well the Frosh are doing. The critic doesn't assign "credit" (or blame) to any particular frosh; instead, it averages it over everyone.

Imagine what would happen if pre-trained Frosh could return year after year to climb the pole! Zambesi makes this possible, by letting us save the neural weights as a sort of "genotype" to pass down information from one Frosh to another. This genotyping is a rudimentary version of the "reproduction" that Cyberlife's "Creatures" perform.

Why Call it "Zambesi?"

Mrs. Zambesi, a "pepperpot" lady in a classic Monty Python skit, ordered a new strap-on brain from Curry's (a department store). The model she chose was called the "Roadster." She even had to undergo a sort of reinforcement learning technique while her brain was being fitted! The Python gang pronounced it "Zam-Bee-Zee."

Can I try Zambesi?

You sure can! I've released a version that gives you a general idea of how the Frosh look when they're under the influence of Zambesi. They will save their weights between games, so that at least for the first few games, the Frosh should improve from one game to the next.

Don't worry - it won't affect your original installation of Legend of the Greasepole. Just install the original version first, upgrade to the J-section version (if you'd like) and then install Zambesi. The original game will work just the same, and you'll have the option to check out Zambesi. If I get the chance to play with Zambesi some more, I'll release additional versions.

As the testing results suggest, the Frosh don't improve indefinitely; in fact, they end up pretty volatile. I mean, if you had to climb the greasepole 250 times, wouldn't you end up a little shaky? You can delete the contents of the "weights" directory (*.wgt) if you want to "reset" the frosh brains.

The In-Depth Stuff

- More Information about Zambesi (below)

- First Round of Testing Data (below)

- About Representing Genotypes of Neural Networks (below)

- Artificial Intelligence vs Neural Networks - what's the difference? (below)

There's a copy of The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks somewhere on the top floor of Goodwin Hall. If you're at all interested in this stuff, you'll love it. Check it out!

References

Barnden, John A., "Artificial Intelligence and Neural Networks" in The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks (Michael A. Arbib, Ed.) pp 98-102.

Barto, Andrew G., "Reinforcement Learning" in The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks (Michael A. Arbib, Ed.) pp 804-809.

Barto, Andrew G., "Reinforcement Learning in Motor Control" in The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks (Michael A. Arbib, Ed.) pp 809-813.

Burke, Robert C., The Legend of the Greasepole Technical Documentation.

Cyberlife Web site, http://www.cyberlife.co.uk.

Haykin, Simon, Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Foundation (1999) 2nd Ed.

Nolfi, Stefano and Domenico Parisi, "'Genotypes' for Neural Networks" in The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks (Michael A. Arbib, Ed.) pp 431-434.

Zambesi: Extended Documentation

ZAMBESI: REINFORCEMENT LEARNING FOR "LEGEND OF THE GREASEPOLE"

Robert Burke, 18 Apr/99

About The Pole Game

The Pole Game begins as 85 artificially intelligent frosh are tossed into the greasepit through a roaring crowd. You view the action through the eyes of a Frec (upper-year student) standing on the bank of the pit. The premise is that you and some of your co-Frecs have noticed that the frosh this year are particularly keen. They'll likely climb the Greasepole in record time, and not learn the teamwork they'll need to survive their upcoming Applied Science education. You have to stall the frosh for as long as possible as they attempt to climb the pole.

As the game progresses, the frosh will learn new tricks, become more resilient to your attempts to stall them, and learn to work together. Should they have problems, they will be assisted by Alan "Pop Boy" Burchell, an upper-year student who jumps into the pit and accelerates their learning process.

The Frosh Character and IntelliFrosh

IntelliFrosh is the behavior-Based Artificial Intelligence engine developed by Robert Burke that governs the behavior of the frosh and other sprites in the game.

The actions of the frosh character break down into 31 behaviors that encompass over 5,000 lines of code. Although the details of these behaviors changed over the course of the project, the core of the artificial intelligence changed very little since its inception in the winter of 1996. After working on IntelliFrosh for a year, the author had a chance to take notes in September of 1997 while watching Science '01 climb their Greasepole. Sample pages of his notes -- mud and lanolin stains included -- are found on the Legend of the Greasepole CD. These observations were used to improve IntelliFrosh's simulation of the transition from chaos to order.

Each of the 85 frosh "thinks" 24 times a second, and there is no "overmind" that controls the horde. They base their decisions on the interaction of over 15 internal characteristics that describe their motivations and their knowledge of the game world.

Overview of Frosh Behaviors

The frosh behaviors are best understood arranged in a four-tiered system. Each behavior consists of an "initialization" function and an "action" function. Every frosh sprite tracks a pointer to the function serving as their current behavior.

The first group of behaviors, numbered 1 through 3, manages frosh under the influence of gravity. The frosh fall with little or no control over their actions.

The second tier -- behaviors 4 through 7 -- manages frosh in the greasepit water. Behavior 4 is a sort of "hub" for the artificial intelligence at this tier. A frosh may make a decision based on internal characteristics and perceived state of the game world to transfer between behavior 4 and behaviors 5, 6 and 7. A frosh exhibiting behavior 7 may choose to exhibit behavior 9 and climb out of the water as a function of their ambition, level of excitement, and knowledge of weight ratios. These characteristics all vary as the game progresses. For example, one way in which the artificial frosh mimic their human counterparts is that they start out keen to climb up the human pyramid. Just about everyone wants to be a hero, and the resulting human pyramid becomes top-heavy. As the game progresses, the frosh learn to exercise caution before climbing up.

The third tier -- behaviors 9 through 14 -- manages frosh dealing with the upper levels of the human pyramid. As they climb, they become influenced by weight on their shoulders, and they apply weight on the shoulders of those beneath them. A significant amount of the learning in the frosh pertains to how they handle situations encountered at this tier in the behavioral structure. Frosh need to know when to stay put and when to climb up. They need to know if they should beckon other frosh up, jump down to reduce the weight of the pyramid, or balance the weight across the level they are on. They need to know not to accept beer and pizza if it's tossed to them, and they need to avoid putting too much weight on the shoulders of any of their compatriots below.

The fourth tier of behaviors manages the various incarnations of behavior 16 -- tugging on the tam. The tam loosens as frosh yank on it in an attempt to get the nails out. A strong tug has a greater loosening effect, but also increases the chances that the frosh will slip. Gnawing on the tam can expedite the process.

The following is a complete list of the behaviors frosh are able to exhibit. Unused behaviors are a result of modifications made to the behavior list during development.

- 1 -- Free-falling into pit

- 2 -- Leaping into pit

- 3 -- Underwater

- 4 -- Wading through pit towards a goal (or target)

- 5: "Fun stuff"

- 5A -- Eating pizza

- 5B -- Drinking beer

- 5C -- Splashing ArtSci

- 5D -- Pushing/Splashing Commie

- 6: "Confusion"

- 6A -- Drunken Singing

- 6B -- Moshing

- 6C -- Swimming Through the Pit

- 6D -- Scratching Head / Communicating / Picking nose

- 6E -- Flying as cow-eagles (Iron Ring effect)

- 6F -- Grazing as sheep (Iron Ring effect)

- 7: "Pyramid Base"

- 7A -- Linking Arms at base of human pyramid

- 7B -- Bucking under pressure at base of human pyramid

- 8 -- Unused

- 9: Climbing up

- 9A -- Climbing over shoulders to a level above the water

- 9B -- Unused

- 10 -- Stumbling over necks towards the pole

- 11: Providing upper-level support

- 11A -- Arms up to support people above

- 11B -- Walking across the pyramid to balance weight

- 11C -- Beckoning other frosh up to this level

- 11D -- Eating pizza up high

- 11E -- Drinking beer up high

- 12 -- Unused

- 13 -- Unused

- 14 -- Clinging desperately to the pole

- 15 -- Unused

- 16: Hanging on to the tam

- 16A -- Reach and yank on tam

- 16B -- Lost grip and hanging off tam

- 16C -- Light tug

- 16D -- Heavy tug

- 16E -- Teeth tug

- 16F -- Holding aloft the tam... victorious!

ZAMBESI: ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND NEURAL NETS?

(If you stumbled across this - I wrote this in 1999 - it's a bit of a time capsule and wild to read, in the context of Claude helping me resurrect this site.)

Neural Nets and AI -- what's the difference?

In order to compare Neural Networks and Artificial Intelligence, we will define AI as follows: the development, analysis and simulation of computationally detailed, efficient systems for performing complex tasks, where the tasks are broadly defined, involve considerable flexibility and variety, and are typically similar to aspects of human cognition or perception. (This definition requires that we include studies like natural language understanding and generation, expert problem solving, common-sense reasoning, visual scene analysis, action planning, and learning under the AI umbrella.)

Note that nothing in our description of AI prevents the computational systems from being neural networks. Indeed, the bulk of AI can be called "traditional" or "symbolic", meaning it relies on computation over symbolic structures. Let's contrast the properties of Symbolic Artificial Intelligence and Neural Networks.

| Neural Networks | Symbolic Artificial Intelligence |

|---|---|

| "Graceful degradation." (There are a number of other properties that stem from this -- the "Pattern completion property" and automatic similarity-based generalization are a result of the same phenomenon.) | Non-graceful degradation. A small change in the inputs to the system often results in significant changes to the output. (This isn't a clear-cut win for Neural Networks. Symbolic AI can be made to degrade gracefully.) |

| Emergent rule-like behaviour. | Typically, non-emergent rules govern behaviour. |

| Content-based access to long-term memory in two senses: (1) The long term memory is in the weights, so manipulating the input vector can evoke memories (2) An output is a particular long-term memory recalled on the basis of the content of the input. | Encodings highly temporary. Rigid long-term memory. |

| Soft constraint satisfaction. | Rigid constraint satisfaction. |

| Difficult to encode multiply-nested structures. | Encoded structures can be multiply nested (nested language understanding). |

| All information of any complexity must be built from lowest-common-denominator structures. | Encodings must allow encoded information to be of widely varying structural complexity. |

| Difficult to encode labelling of links and understand how a decision is made. Programs can't be stored in any conventional sense. | Links, pointers and stored programs can be created. |

| Resolution of Neural Network activation values not fine enough to allow them individually to encode complex symbolic structures. | Resolution not an issue. |

| Learning proceeds in lengthy, gradual weight modification. | Can perform certain types of rapid learning, proceeding in large steps. |

Open Questions

Is it necessary to go beyond symbolic AI to account for complex cognition. If so, should we throw away symbolic AI entirely? Or is some amount of complex symbol-processing unavoidable? Moreover, how can different styles of systems be gracefully combined into hybrid systems? The truth is out there...

References

Barnden, John A., "Artificial Intelligence and Neural Networks" in The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks (Michael A. Arbib, Ed.) pp 98-102.

Haykin, Simon, Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Foundation (1999) 2nd Ed.

Genotypes for Neural Networks

Two years ago, a UK-based company, Cyberlife, unleashed a game called Creatures onto the PC platform. When both Oxford geneticist Richard Dawkins and Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy author Douglas Adams praised it as a scientific and artistic masterpiece, it helped me justify the amount of my time it was consuming. This was "real" artificial life: characters called Norns that had neural networks for brains, were capable of interacting with their peers and the user, and used a genetic algorithm and "digital DNA" to allow for mating and reproduction. They looked like a cross between "a deer, a cat and a hamster" and were, well, pretty cute. You taught them to eat when they were hungry, to sleep when they were tired, and to avoid all sorts of peril in their two-dimensionally rendered little world. As crazy as it may sound, if I had to pick the single most significant influence on my decision to study Synthetic Characters at MIT's Media Lab next year, it would have to be Creatures.

Creatures raised more questions than it answered. Because it is a commercial product, its creators are understandably high-level about what makes their creations tick. Dr Bruce Blumberg, head of the Synthetic Characters group at the Media Lab, suggested to me that there's probably "less to Creatures than meets the eye." That's probably true, but it doesn't take away from what might evolve from products like Creatures.

I was interested to find Stefano and Parisi's article in the Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks that addressed the issues of how to encode the "genome" of an artificial creature. They introduce their article by discussing the elements we might find in the genotype of a neural network. These elements might include any or all of the following:

- The network architecture

- The initial weights

- The learning rates and momentums

To create a "genotype," we need to somehow encode this information into a string that can be passed between generations. In so doing, we tend to depart from the biological underpinnings. The architecture of a neural network is typically encoded by specifying which neurons connect to which other neurons. This is a far cry from a three-dimensional physical reality, where neurons close to each other in 3D space are more likely (but not guaranteed) to form connections.

Nolfi and Parisi propose a new technique that more closely models the brain's development. They create organisms they call "Os" that search for food in an artificial environment. Their life-span is finite and pre-ordained (which isn't very lifelike, really), and the one-fifth of the organisms that eat the most food over their life-span are allowed to reproduce agametically, which means they simply generate five copies of their genotype. Random mutations are introduced into the copying process by replacing 20 of their 40 genotype bits with randomly selected values.

Each of the 40-genotype blocks has five components that encode the following information:

- Whether or not the neuron exists at all

- The (x, y) co-ordinates of the neuron in 2-D space

- Branching angle of the axon

- Segment length of the axon

- Activation bias or threshold of the neuron

Neurons were grouped into three groups: sensory (5), motor (5) and internal (30).

The first incarnation of the Os didn't learn at all during their lifetimes. Their behaviour was entirely genetically transmitted. This differs from the Norns of Creatures, who learn from the user and their peers throughout their lives. Nolfi and Parisi sought to discover how learning during a creature's lifetime would affect the evolutionary process.

To do so, they split the network into two parts: the "standard" network, and a "teaching" network. Both networks shared the same input units, but had separate sets of internal and output units. The standard output still generated motor actions, and the teaching units were equipped with pre-ordained network parameters that were considered to be "good." Using a back-propagation algorithm with a learning rate of 0.15, the "teaching" network schooled the standard one. With this modification, evolution tended to favour Os that had a predisposition to learn, and not the ones that started their lives in the best shape for acquiring food. Interestingly, their performance at birth did not increase across generations; instead, what increased was the ability to learn the desired performance.

Nolfi and Parisi may have come closer to a genotypical model that takes into account the location of neurons in a three-dimensional space, but they've also strayed a few steps further away from a "real life" model:

- Forcing creatures to each live the same lifespan is unreasonable, particularly when their performance is based on their ability to acquire presumably life-sustaining "food."

- The tremendous amount of mutation that happens between each generation is also unrealistic. Whereas far less than 1% of the genes in a mammal undergo a mutation between generations, here a full 50% are mutated.

- We are given no indication of how they arrived at the pre-ordained "teaching network." Living organisms don't have the equivalent of a "Schaum's Outline" guiding their evolution! Within their genetics, the Os already have bestowed upon them a genotype they are to consider "ideal." Not only does this discourage creativity and push Os towards a single pattern, but a parallel doesn't exist in the real world.

- The authors concede that they are also missing a model for the mapping between genotype and phenotype (ontogeny), which Cyberlife claims it has already deployed within its Norns.

The results Nolfi and Parisi obtained are interesting, but to generalize their results beyond the realm of their "Os" would be unrealistic. The notion that "ability to learn" is more important than "what you are already encoded with" is an appealing one, but I certainly don't think any correlations could be drawn between these artificial creatures and traditional living beings, or even the Cyberlife Creatures.

Cyberlife's creatures have similar limitations:

- The Norn brains intrinsically group objects into categories like "food," "toys" and "lifting devices." Regardless of how the user tries to train them, they are forced to associate objects with one (and only one) of these groups. So, you can teach a Norn to eat "food" when it is hungry, but you can't teach it to eat carrots and not cake.

- The Creatures don't have an "ideal" genotype like the Os, but they are provided with a "computer console" within the game is can be used to teach the Creatures a set of about a dozen verbs. These verbs are also pre-programmed into the system. Norns have no way except by using the computer to learn the meaning of a verb, which is perhaps as much a fault of the interface as anything else. It would certainly be difficult in a point-and-click environment to teach the meaning of the word "eat," for example.

Both Norns and Os provide exciting starts towards artificial life. It is clear, however, that there is a long way to go. As for the Norns, it would appear that the rigidity of the input-output relationship in their neural networks is a stumbling block. In Nolfi and Parisi's case, they take one step towards more authentic artificial life, and three steps away from it. Perhaps genetic algorithms and neural networks are not the only tools we will need to use if we wish to create authentic artificial life.

References

Cyberlife Web site, http://www.cyberlife.co.uk.

Nolfi, Stefano and Domenico Parisi, "'Genotypes' for Neural Networks" in The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks (Michael A. Arbib, Ed.) pp 431-434.

Haykin, Simon, Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Foundation (1999) 2nd Ed.

ZAMBESI: TESTING, ROUND 1

Robert Burke, 22 Apr/99

That's all great, but how does it perform?

After implementing Zambesi and reading about genetic algorithms, I was curious to find out whether or not I could "breed" more intelligent frosh for Legend of the Greasepole. A set of 85 randomly-generated Frosh that were created with the original Zambesi implementation could take anywhere up to three hours of game time to climb the Greasepole on a particularly bad trial.

In order to continue testing Zambesi, a number of modifications to Legend of the Greasepole's code were necessary. First of all, a modification to the main code loop allowed the game to process the Artificial Intelligence of the Frosh at full speed, neglecting sound and graphics output. A three-hour greasepole climb could now be "run" in less than four minutes on a Pentium-II at 233MHz. In accordance with this change, all climb time scores in this document are reported in iterations. One iteration is 1/23rd of a second. Information about each trial is saved to the polegame.txt file in the Legend of the Greasepole directory.

Zambesi's Roadster class was extended to include a system for saving and loading neural network weights. This serves as a rudimentary method for transferring weights between generations of Frosh. All Frosh have the same learning rate h within a generation; this learning rate could theoretically change from generation to generation, or even within the course of a greasepole climb. While we have provided no means for encoding the learning rate (or the structure of the neural network) within the genotype, these would be interesting venues for future research.

Round 1 Conclusions

Two millenia of Greasepole climbing later, I arrived at the same conclusion as Nolfi and Parisi in their article 'Genotypes' for Neural Networks. Frosh that began their lives with neural networks that had previously produced exceptional results were not particularly more prone towards additional rapid victories. Nolfi and Parisi went on to say that it was the ability to learn that improved a creature's performance. It is unclear how we could test this in the context of the greasepit.

Passing information through genotypes

Consider the results of Trial 8D below, which was performed by first saving the weights for 250 generations of Frosh. Each group of 85 frosh simply inherited the weights of their 85 "parents." It would have been very difficult to isolate which Frosh in the pit are contributing the "most" to a successful Pole Climb, and so we did not employ a Natural Selection algorithm. For 8D, we took the weights of the Frosh that had the best pole climb time, and had those Frosh try to climb the pole an additional 48 times. Their average time -- 31275 iterations, or just over 22 minutes game time -- was impressive when compared to the averages across all trials. However, these results had a standard deviation of 25,978, and their climb times varied from 5,405 iterations (less than 4 minutes) to over 118,000 iterations (85 minutes). It would seem that "exceptional" groups of Frosh are also exceptionally volatile, and they can be easily influenced by random events that affect their climb.

While maintaining neural weights from one generation to the next did produce better average climb times, this isn't evident in the results of trial 9. Perhaps a more interesting way of observing the effect that passing information through generations had is the graph shown below. This figure shows how the groups of Frosh tended to improve and decline in waves. It is possible that this is the result of the Frosh encoding "noise" in their weights.

Zambesi as an Input-Output Model

Average pole-climb times for Frosh using the old system were considerably less than 30,000 iterations (6,900 iterations or 5 minutes of game time was common). These tests suggest that we have not provided our neural network with the inputs it would require to produce more effective outputs. Consider some of the relationships that it might be helpful for a neuron to be able to encode. For example, the reasoning, "there are two of us on this level, so I will support you, and you can climb up" is not a thought that would be possible within the context of the current neural network. The thought could be "hacked" if, due to randomness, one of the Frosh elected to climb up, and the other elected to stay put. But hinging such critical behavior on something so random seems inappropriate.

Zambesi as a Critic Model

The Zambesi Critic algorithm is too simple. Consider the situation where a Frosh is actively tearing on the Tam. From the moment the Frosh reaches the Greasepole until the moment the pyramid tumbles and is being rebuilt, every Frosh in the game is being told their behavior is producing failure. This is inane. Something needs to be done to reward the Frosh for stable pyramids that reach the tam.

The Legend of the Greasepole as a Learning Environment

Training 85 neural networks to create 85 characters that are meant to work in unison is a difficult and interesting challenge. I am adamant that there must be some way to train uberFrosh that perform better than the artificial intelligence I wrote for the release version of Legend of the Greasepole.

Postscript

An examination of the weights of higher-generation Frosh suggests that the high failure-to-success ratio in the pit produces Frosh with extremely negative neural weights. Research is continuing with new critic models and learning algorithms to prevent this.